Spearcons and the spectrum of speech comprehension…

We are fortunate to have an amazing advisory board filled with diverse expertise in many sectors and who bring diverse lived experiences. On a recent advisory board meeting, I learned about a new term for how we use and define spearcons — an invited term called “nearcons.”

To backup and provide context, a spearcon “is a brief sound that is produced by speeding up a spoken phrase (often a synthetic TTS phrase), even to the point where the resulting sound is no longer comprehensible as a particular word” (Palladino and Walker, 2007).

In our auditory display work, I have grappled with the perceptual and speed threshold related to spearcons and speech. At what % speed increase for speech needs to occur before speech is labeled as a “spearcon”? What speed increase would best fit our target audience (BVI learners)? In our year 1 development, I generated TTS phrases and sped them up to over 200%. The speed determination was based partly upon spearcon definitions and settings found in speech readers. In playback of auditory display prototypes this month to our advisory board, we were advised that it was perfectly fine to crank the speed of our ‘spearcons/nearcons’ to 400% (or more), such that we could no longer recognize the speech.

We already knew about research showing positive learning rates for spearcons in auditory menus (Nance, Lindsay, and Walker, 2006; Palladino and Walker, 2007) and learnability over earcons (Dingler, Lindsay, Walker 2008). I simply wasn’t sure where the threshold existed for when spoken phrases become “spearcons.” Our current speeds were labelled as “nearcons,” because the text was fast, screen-reader fast, yet still intelligible as speech.

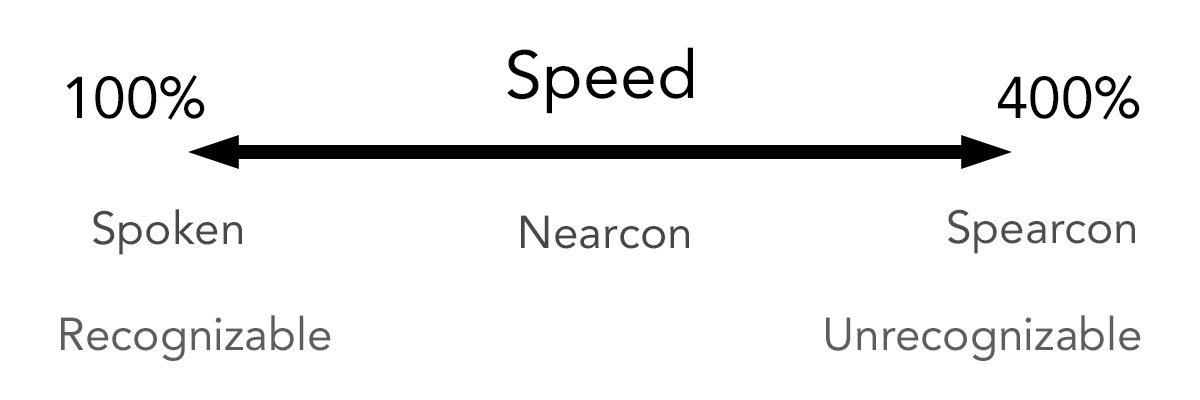

To help provide further clarity around a perceptual threshold that is often depicted in articles as “even to the point where” speech is no longer recognizable (Palladino and Walker, 2007; Walker and Nees 2011), we offer a short history of definitions and a speed spectrum (Figure 1). The spectrum in Figure 1 depicts how the speed of a spoken phrase, whether a human recording or a synthetic TTS phrase, shifts into spearcon territory based upon speed. We recognize this is a reduced depiction using only speed as a threshold and does not account for the wonderful differences in pscyhoacoustics, culture, and learning. This spectrum comes from our own experiences and feedback in generating auditory displays and does not necessarily depict actual speeds used in research studies with spearcons.

Figure 1. Speech speed spectrum, where slower speech is recognizable and faster speeds become spearcons as comprehension decreases.

Audio Example. TTS synthesized speech saying "Day One", is played from 100% to 600% to demonstrate the spectrum of comprehension as it relates to spearcons.

References

Walker, Bruce, Amanda Nance, and Jeffrey Lindsay. “Spearcons: Speech-Based Earcons Improve Navigation Performance in Auditory Menus.” In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Auditory Display. London, UK: International Community for Auditory Display, 2006. https://smartech.gatech.edu/handle/1853/50642.

Palladino, Dianne K., and Bruce Walker. “Learning Rates for Auditory Menus Enhanced with Spearcons Versus Earcons.” In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Auditory Display, 274–79. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: International Community on Auditory Display, 2007. http://hdl.handle.net/1853/50011.

Dingler, Tilman, Jeffrey Lindsay, and Bruce Walker. “Learnability of Sound Cues for Environmental Features: Auditory Icons, Earcons, Spearcons, and Speech.” In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Auditory Display. Paris, France: International Community for Auditory Display, 2008.

Raman, Parameswaran, Benjamin Davison, Myounghoon Jeon, and Bruce Walker. “Reducing Repetitive Development Tasks in Auditory Menu Displays with the Auditory Menu Library.” In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Auditory Display. Washington, D.C.: International Community for Auditory Display, 2010.

Walker, Bruce N., and Michael A. Nees. “Theory of Sonification.” In The Sonification Handbook, edited by T. Hermann, A. Hunt, and John G. Neuhoff, 9–39. Berlin, Germany: Logos Publishing House, 2011.

Learn More

Learn more about spearcons as x-axis markers.

Learn more about inclusive design: sonic graph divisions.

Learn more about earcons as sonification bookends.

by Jon Bellona